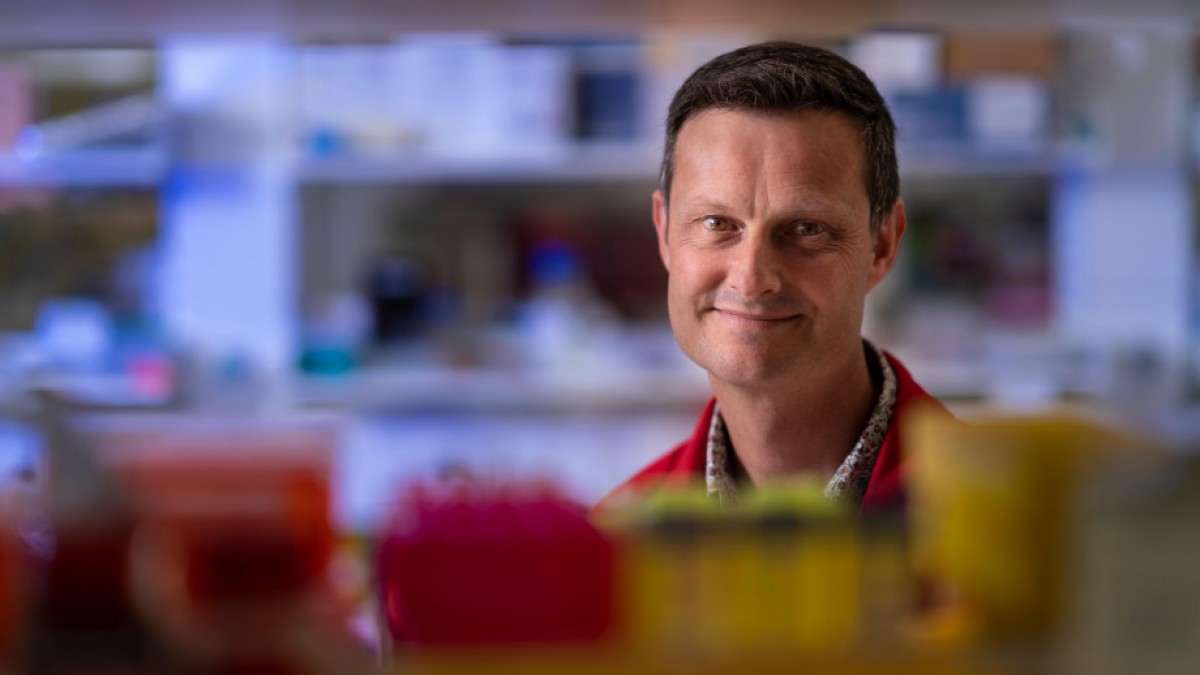

Professor David Tscharke was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) at 41, after he noticed some tingling and numbness on the left side of his body.

"I knew something was wrong because I had an odd sensation in my left arm and then some numbness in my left hand and then tingling in my left foot," Professor Tscharke, from The Australian National University (ANU), says.

"As a medical researcher, you know there is only one thing that connects the hand and the foot and that is the central nervous system - so that made me worried. I went to my GP and had an MRI."

Professor Tscharke has spent the past 30 years of his career dedicated to understanding virus and immune responses, and he is now tackling MS in the lab and in his life.

At 51, he has been living with most common form of the disease, relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), for almost a decade. Professor Tscharke has regular treatments and he wants to improve them for everyone.

"I want to help people with MS, like me, make better treatment option choices," Professor Tscharke says.

"Everyone responds to MS medications differently, so I have been looking at devising a method for early identification of response to treatments - both suppression of MS activity, and infection."

RRMS is caused by the immune system mistakenly attacking the myelin that insulates nerves to help them transmit their signals accurately and quickly.

It is characterised by acute episodes of acquiring symptoms - which can greatly vary and are different for everyone - including numbness, being unable to walk or, loss of vision. The symptoms can last for days or months, then they remit and can sometimes go away completely.

Professor Tscharke has been awarded an Incubator Grant from MS Research Australia for a new approach to treatment for RRMS that he's developed.

His novel approach examines the RNA in the blood of people with MS who are being treated with the disease modifying therapy Cladribine.

"A strength of the project is that we are following a group of people with MS who we are sampling regularly and pairing the results to their clinical condition at the time and data from another project that is ongoing," Professor Tscharke said.

"We can see how things are changing their blood in real time, and then if there is any relationship between that and what the neurologist is seeing.

"We are aiming to understand how this treatment works and identify evidence of early success at a molecular level."

The analysis will also determine whether some infections increase in response to therapy before they cause symptoms, because these can be a problem in the future.

By looking at the RNA in patient's blood, researchers will be able to simultaneously track how the immune system is functioning and the presence of infections.

Dr Julia Morahan, Head of Research at MS Research Australia says, "We are delighted to provide funding to Professor Tscharke's novel idea investigating RNA sequencing to detect MS treatment success and rapidly detect opportunistic infections.

"We hope that innovative strategies like this will help optimise treatment for individuals and ultimately improve the lives of people with MS."

Looking in the mirror

This new approach to MS research has come with a mirrored response for Professor Tscharke in his own life.

“The timing is almost beyond belief. I am starting a new project to research infections associated with treatments for MS and I've just found out that I have caught a virus infection that means my current MS treatment is no longer safe,” Professor Tscharke says.

“I have to change my treatment and there is always uncertainty when you change your treatment. There are a number of options and it is a difficult choice people with MS have to make with their neurologist and treatment teams.

“One of the downsides of the most effective medications for MS is that they dampen the immune response, thereby increasing the risk of infection.

“Another issue with MS treatment is that it is difficult to know for sure whether a medication is working.

“The evidence is very strong that the treatments work very well as a general rule, but every person with MS is different.

“As a scientist, I understand the evidence and expect my treatment will keep my MS quiet, but I am still anxious each time I have an MRI scan of my brain to check for disease activity, or I notice an unusual muscle twitch or something.”

Professor Tscharke says he found it hard to shake the idea that things would go downhill quickly after a brief period of double-vision in the first year after his diagnosis.

Things stabilised, and he says finding the right treatment helped. He was able to resume his work as a leading virology and immunology researcher.

“The irony of researching the exact thing I am experiencing is not lost on me,” he says.

“Being a medical researcher helps me navigate MS, but it doesn't remove the emotional component of all of this, and having a chronic disease is a particular burden in your mind.

“I have symptoms all the time to remind me that something is not quite right, but I know that my journey with MS has been better than for many.

“Having MS is drawing a short straw in life, but having MS that's not highly active – it is a little bit of luck.”