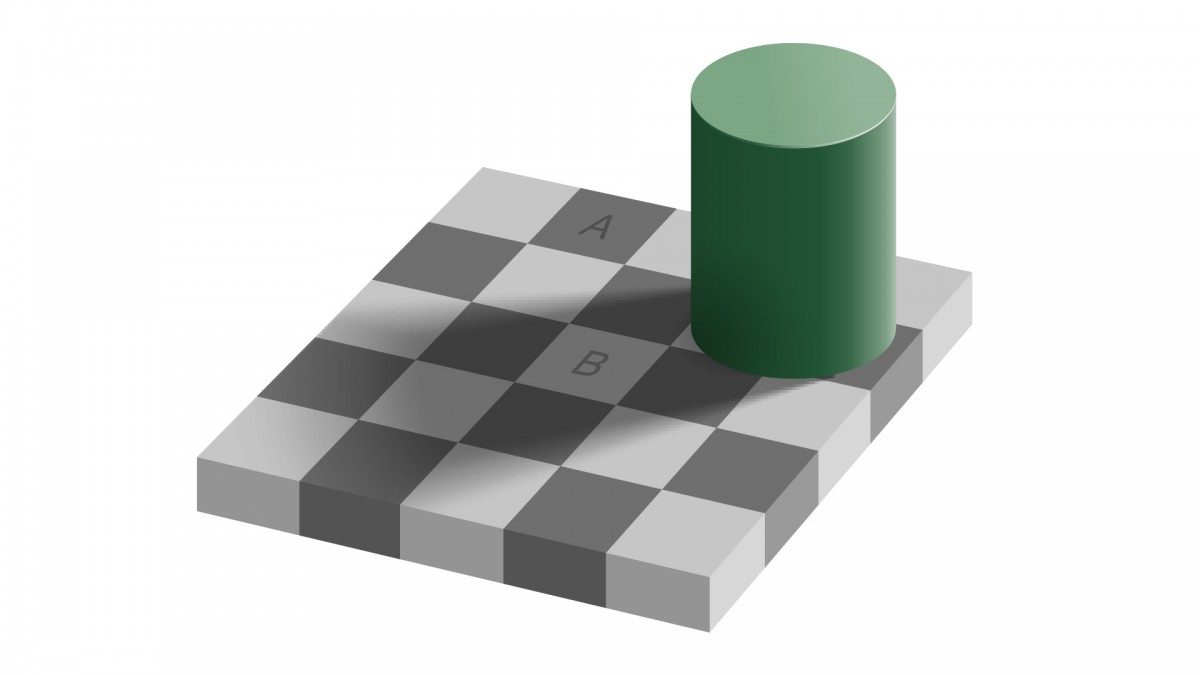

Illusions are both intriguing and fun, and for the past century have played a significant role in brain research. Take an illusion in the form of colour representation, for example, where you might ask, is one colour the same as the other? Or a rotating dancer, is the dancer spinning left, or right? Or both? While such illusions are commonly used to entertain, they also help to unravel some of the mysteries of the human brain studied by neuroscientists, psychologists, and philosophers alike – how we create a ‘reality’ or a representation of the external world; how we perceive things; and at a more fundamental level the relationship between perception and reality.

In a first of its kind in Australia, ANU is offering a single degree program – a Bachelor of Philosophy, Neuroscience and Psychology (BPNP) – that provides a unique opportunity for undergraduate students to explore the complex relationships between mind and brain through a transdisciplinary lens.

Traditionally these degrees are taught and practised as separate disciplines. Experts tend to specialise in a particular set of questions: philosophers on human enquiry, psychologists on the mind, and neuroscientists on brain mechanisms. By bringing the three disciplines together from the outset, students will be challenged to think differently, interrogating fundamental research questions across the three disciplines.

Neuropsychologist and Course Coordinator, Associate Professor Anne Aimola Davies teaches Neuropsychology and Cognitive Neuroscience at ANU, a course that paves the way for multidisciplinary thinking.

“Experimental cognitive psychology is very much a theoretical scientific pursuit, and we are often referred to as cognitive neuroscientists, as we look at the way that brain structures and networks underpin sensation and perception, attention and consciousness, memory, thought and language.

“We are teaching our students to be experimental psychologists from day one. This means setting up a novel research question, conducting a review of current literature in the research area, generating hypotheses that can be tested, participating in an in-class experiment, and learning to write up an associated laboratory report.

“It’s not that psychology doesn’t already connect with philosophy and neuroscience, but we are certainly not connecting enough. What is exciting about the BPNP degree is that we will be working on the same topics and the same issues in the same room together, which takes these connections to a whole new level.”

Philosopher and Course Coordinator, Professor Colin Klein believes there are uncharted territories when it comes to the mind and brain relationship.

“One might argue that many problems we face in the world are not necessarily technological problems. Or political problems. They're problems with how we think and how we understand each other. As a society we have much to gain from a collaborative approach where the commonality is the question and teams are working together to find solutions.

“Take the concept of pain or mental health and its treatment, pharmaceutical or otherwise. We need the collective clinical and scientific knowledge of the brain and how it functions, the criteria for diagnosing of a mental health condition and how it is defined, and we need to understand what is meant when people talk about ‘feeling bad’. The mind is complicated, and you can’t just look at it from one perspective.”

But it is not just matters of human health that can benefit from this approach. This same concept can be applied, to say, Artificial Intelligence, where we might question its (human) abilities to be ‘creative’. What do we mean when we say ‘human’ and ‘creative’? What is the linkage of imagery to our cognitive processes, and what happens in the brain when we are forming new ideas and connections, and how that compares at a computational level to Chat GPT.

Neuroscientist and Program Convenor, Professor Ehsan Arabzadeh, anticipates that the BPNP will chart a new path for both students and academics.

“It’s a rare opportunity, particularly at the undergraduate level – the students will be formulating ideas, running experiments and simulations, and working side-by-side with scientists in our wet labs.

“Our graduates will gain analytic skills to critically evaluate theoretical and experimental approaches from multiple perspectives, both big picture and detail, and will learn to apply these skills to real-world problems. It is a dynamic field that enables multidisciplinary experience in one person,” says Ehsan.

With advances in data science, being able to move between these perspectives is a valuable skill. As well as being well-positioned to undertake further study in any of the three discipline areas, students could find themselves on a new wave of careers in science, in areas such as research, consulting, behavioural analysis, policy development, user-experience, education, politics, and working in the public and private sector.

“Momentum is already building, says Anne. “Some of our current psychology students already do courses in philosophy or neuroscience, and there is a genuine excitement for the combination of these three disciplines in the new BPNP degree – and a wish that they could have done it!”

The Bachelor of Philosophy, Neuroscience and Psychology draws on ANU strengths in philosophy, neuroscience and psychology and its world-class facilities, scholars, and scientists.

The BPNP, a joint degree program with the ANU College of Health and Medicine and the ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, is now accepting applications for a 2025 student intake.