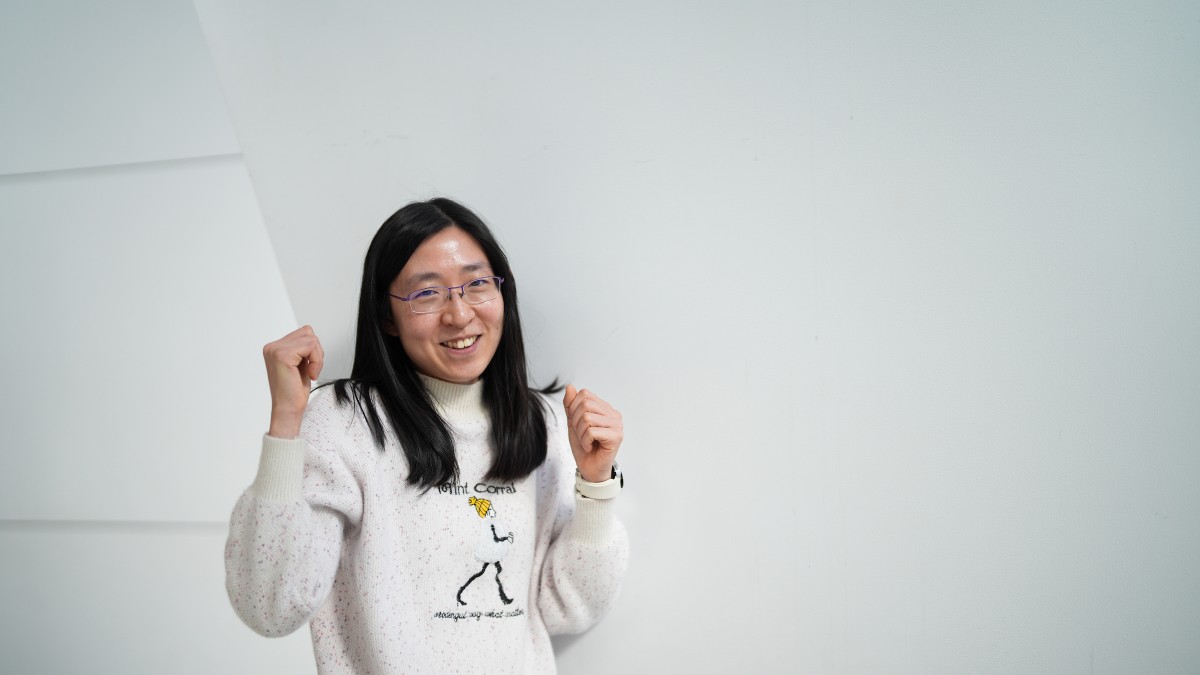

Dr Alice Richardson wants to help doctors give the best advice, by helping them determine the severity of their patients’ ME/CFS symptoms.

“I've been looking at patterns and profiles of combinations of symptoms,” she says. “Combining these results with a test where people stand up for a set amount of time and rate the difficulty of this task, allows us to categorise symptom severity into mild, moderate and severe.”

Using powerful statistical methods, the team at ANU has also looked at the results from routine pathology tests. They did find potential biological markers for ME/CFS, and interestingly these are hiding within the ‘normal’ ranges of these tests.

Although these results are promising, Dr Lidbury heeds that because the sample size was so small – 100 people from the same geographical location – more work is required before they can develop diagnostic guidelines for doctors.

“As scientists, we need to look at the broader picture by repeating our observations at a much larger scale,” says Dr Lidbury. “This is where the biobank comes in.”

The new biobank will provide researchers with access to blood samples and DNA from people with ME/CFS.

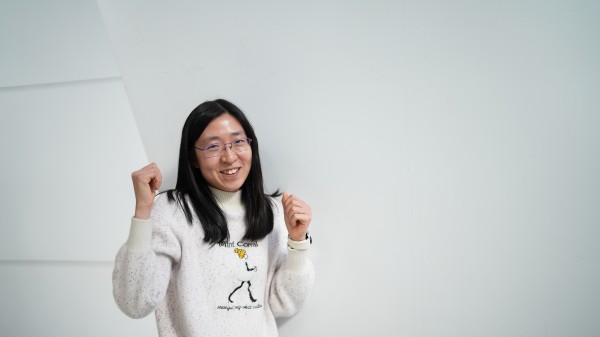

As a biostatistician, having access to more data makes Dr Richardson very happy.

“At the original funding announcement, there were people writing in, saying ‘please take my data’, ‘collect my data’, which is fantastic,” she says.

“By increasing the sample size, we can get much more powerful results.”

Funded by The Mason Foundation, and recently announced by project leaders at La Trobe University, this new $1 million research partnership, will also support collaborators in Australia, the UK and North America and Emerge Australia.

“There's a need to start pulling in data from other areas,” says Dr Richardson. “That's why this team includes people looking at everything from the whole person, right down to gene sequences and the individual parts of cells.”

Dr Lidbury is grateful for the ME/CFS advocates and patients who have campaigned for more research funding in Australia, and hopes that a new diagnostic test will help address some of the discrimination people are facing.

“I think the answer is already in the room. It just needs to be validated,” he says.

“With validated results, we can start educating GPs about new ways to make a diagnosis.”

As GPs are already under so much pressure, Dr Lidbury says that having the tools for them to refer their patient to someone who knows more about the condition, is an important step in the right direction.

“At least it’s a lot better than effectively saying, ‘It’s all in your head’.”

If you would like to get involved in the patient registry and biobank, either as someone with ME/CFS or as a healthy control, please visit the Emerge Australia website.